Bottom line: Scientists have spent decades trying to understand why the Sun's outer atmosphere is vastly hotter than its surface. Solving this mystery is one of the primary goals of the Parker Solar Probe, a spacecraft designed to approach the Sun closer than any other human-made object. Recent data from the mission has ruled out one popular theory.

Scientists have long detected superheated and ionized iron in the Sun's rays. However, heating this element to such a degree requires temperatures exceeding two million degrees Fahrenheit, which suggests that the corona – the Sun's upper atmosphere – is over 200 times hotter than the 10,000 degrees detected at its surface. This paradox, known as the "Coronal Heating Problem," has been a central topic of debate in solar science.

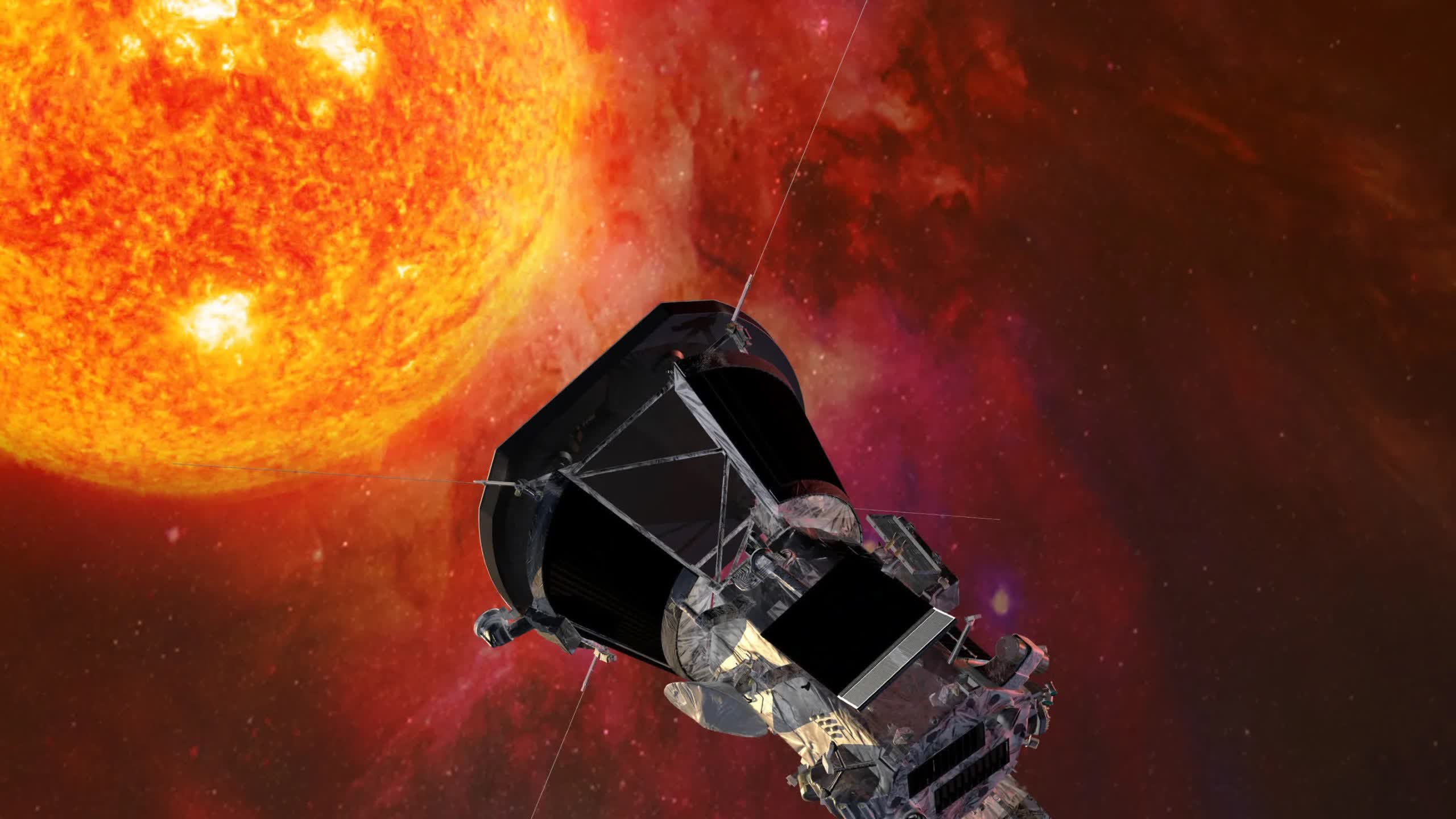

In 2018, NASA launched the Parker Solar Probe to investigate this and other questions. Designed to withstand extremely close encounters with the Sun, the probe entered the Sun's atmosphere in 2021 and has since been transmitting the most precise solar measurements ever recorded.

One detail the mission confirmed is that the corona's boundary isn't smooth but rather bumpy. Last year, the probe also discovered numerous small jets that might be the driving force behind solar wind, similar to how individual claps combine to form a loud applause.

A new study based on recent Parker Solar Probe data confirms the absence of what scientists call "switchbacks" in the corona. Switchbacks are components of magnetic fields that could potentially energize the transfer of heat. Scientists had theorized that they might play a role in coronal heating, especially since the Parker Probe detected switchbacks in the solar wind emanating from the Sun.

The study, conducted by the University of Michigan, establishes that switchbacks aren't generated within the corona, likely shifting scientists' focus toward other potential explanations for the coronal heating mystery. One theory suggests that turbulence beyond the corona could affect the magnetic field. Meanwhile, some scientists believe that explosions called nanoflares – smaller versions of solar flares – might be responsible for coronal heating.

Currently engaged in an elliptical orbit around the Sun, the Parker Probe is scheduled for another close approach to collect more valuable data on December 24.