Forward-looking: Oxford University researchers have developed a flexible perovskite material about 100 times thinner than a human hair that can generate solar electricity just as efficiently as traditional silicon panels. Unlike those rigid, single-purpose slabs, this material can coat just about any surface, such as cars, clothing, buildings, and even mobile devices.

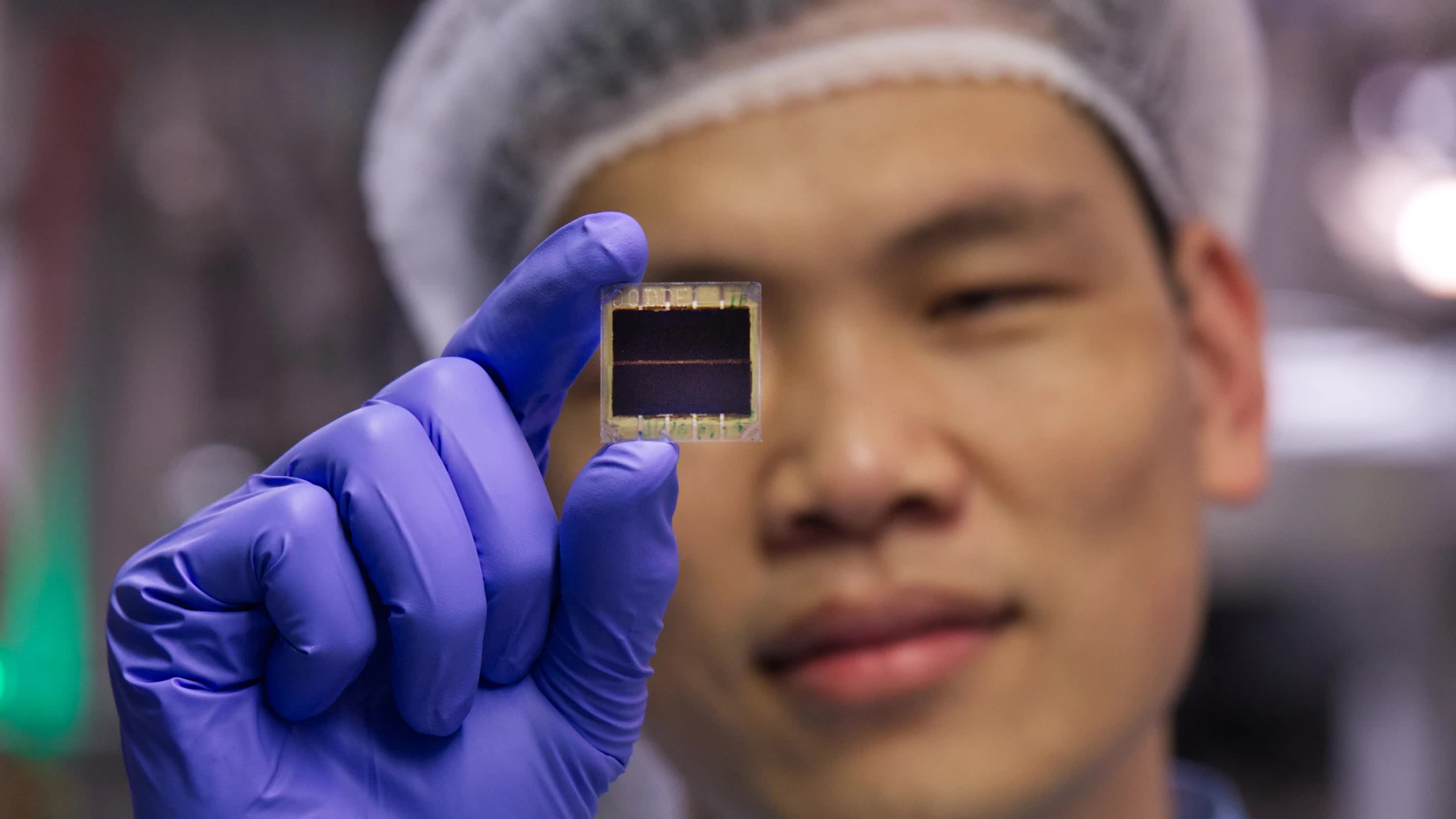

Scientists at Oxford University Physics Department have developed a groundbreaking solar-power innovation. They have miniaturized solar panels that are thin enough to print on any object while maintaining comparable energy output.

Using a pioneering technique, the scientists can stack multiple light-absorbing layers into a single solar cell. A "multi-junction" approach allows the material to harness a broader light spectrum range, generating more power from the same amount of sunlight. This new material has already been certified at over 27 percent energy efficiency by Japan's National Institute of Advanced Industrial Science and Technology. That matches the performance of conventional silicon photovoltaics.

"During just five years experimenting with our stacking or multi-junction approach we have raised power conversion efficiency from around 6 percent to over 27 percent, close to the limits of what single-layer photovoltaics can achieve today," said Dr. Shuaifeng Hu, a member of the Oxford team. "We believe that, over time, this approach could enable the photovoltaic devices to achieve far greater efficiencies, exceeding 45 percent."

It's even more impressive considering the material's thickness. It's almost 150 times thinner than a silicon wafer at just over one micron thick. Its flexibility means solar power is no longer tethered to rigid panels and solar farms that occupy vast swathes of land, potentially reducing our dependency on them.

The researchers envision a future where perovskite solar coatings are everywhere, a hope assisted by plummeting solar panel costs. It's already almost a third cheaper than fossil fuels after a 90-percent price plunge since 2010. Solar and wind power generation also hit record highs last year, providing 12 percent of global electricity, so the principle of economies of scale could also be at play here.

The breakthrough holds strong commercial promise, too. Professor Henry Snaith's photovoltaics team is among the pioneers of perovskite research over the past decade. Their work already spun off a UK company, Oxford PV, which opened the world's first perovskite-on-silicon solar manufacturing line in Germany.

"We originally looked at UK sites to start manufacturing but the government has yet to match the fiscal and commercial incentives on offer in other parts of Europe and the US," said Snaith, lamenting that they couldn't build the plant in the UK.

He added that "real" growth will come from commercializing innovations. He hopes British Energy, a governmental investment body, will focus on his team's breakthrough.

Image credit: Martin Small